The Libya Chapter

The Libya Ambivalence

Toward a Shallower Ambivalence

Libya: He's a Rebel

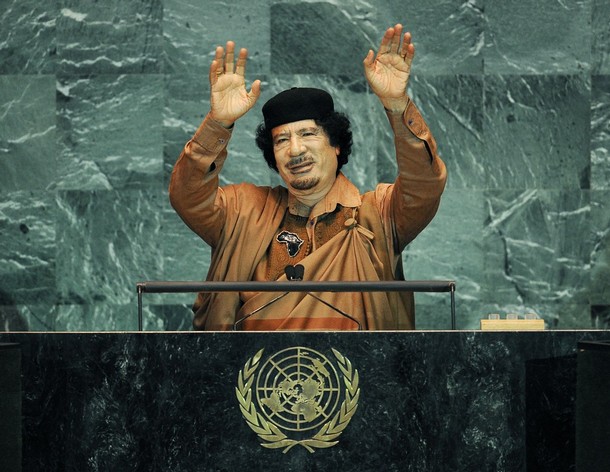

The president spoke last night and flatly asserted that this would be a better world without Qadaffy running Libya. And one of my principal misgivings is that there's no guarantee that that's true. Given the charges of racism, extremism and atrocities on the rebel side – let alone the number of rebel leaders who recently defected opportunistically from Qadaffy's government – the eventual outcome is a crapshoot by any measure.

Professor Juan Cole recently dismissed concerns about the rebel alliance with a wave of his hand, calling it a libel against the people of Misrata and Benghazi. Cole's "Open Letter to the Left" has been countered by BooMan and by Steve Clemens – the latter in the context of grudging support for the intervention, the former in ambivalent opposition.

For my part, I know that Cole knows more about the Middle East than I ever will, but I'm not entirely convinced by his characterization of extremist elements as "a handful" of those fighting for regime change. And even if so, what we saw in Kosovo was that war criminals make better fighters than pacifists, tend to get the backing of intervening powers, and are better equipped to police the outcome and dictate terms.

The flip side of concerns about the rebels is that despite an indefensible record on human rights, it seems Qadaffy still retains considerable support within Libya. While it's true that any dictator who holds power for 42 years will have found ways of developing a base of loyalists. there may be other reasons Libyans are willing to fight on Qadaffy's behalf.

Colonel Q was a good guy to Nixon and Kissinger when he first swept aside the British-backed King Idris. He morphed into a bad guy during the oil embargoes, then became a really really bad guy during the Reagan years. He had to be deputy bad guy during the Bush-Clinton-Bush years as Saddam took the top slot. Then, after paying blood money for Lockerbie, he became a guy we could do business with during the late Cheney regency. Now he's our number one Hitler again, despite the list of viable alternate contenders.

There are some, however, who are not shy about pointing out redeeming aspects of the Qadaffy regime. The Libyan standard of living stands in marked contrast to that of, say, Yemen (responsible opposing viewpoints here, here and here). It also appears that, unlike many dictators, Qadaffy is willing to arm his populace – a move he may yet come to regret.

Stephen Zunes, professor of peace, while no fan of the man, nevertheless reminds us:

As mercurial and repressive as Qaddafi is, he still has a social base. It is not just foreign mercenaries that are keeping him in power. In his 41 years as ruler, he wrested the country away from neo-colonial domination, instilled a sense of national pride and - despite his mismanagement and capricious policies - led his country to achieve the highest Human Development Index ranking in Africa, surpassing scores of relatively wealthy non-African countries as Saudi Arabia, Bulgaria, Serbia, Mexico, Costa Rica, Malaysia and Russia. There are many Libyans who, while unhappy with Qaddafi's rule, are not ready to support the opposition.

Professor Elleni Centime Zeleke in "Libya: The Poverty of Analyses," adds this:

Did the Ghadaffi regime change the structures of society in any significant manner? Yes it did. Did the regime defend certain progressive ideas/policies, such as land reform, better prices for oil, massive decrease in child mortality rates, better distribution of wealth and access to state institutions of caring? Yes again. Will it be very difficult to maintain these gains in the present neo-liberal conjuncture? Will it be even more difficult to maintain these gains in a post-Ghadaffi era with a political arrangement that invited imperial forces into the country in the name of human rights? More likely it will be very difficult.

Over at Dissident Voice, Gerald Pereira offers a full-throated defense, which, while glossing over any unpleasantness, helps explain support for Qadaffy in sub-Saharan Africa:

One of Muammar Qaddafi’s most controversial and difficult moves in the eyes of many Libyans was his championing of Africa and his determined drive to unite Africa with one currency, one army and a shared vision regarding the true independence and liberation of the entire continent. He has contributed large amounts of his time and energy and large sums of money to this project and like Kwame Nkrumah, he has paid a high price.

You don't have to buy into the paradigm of Qadaffy as the godfather of African liberation movements, or a social democrat on the Scandanavian model, to conclude that many will support him for what they perceive as rational self-interest. All three of the above writers are worth checking out in full in order to understand the potential ramifications of this intervention.

When the president spoke last night, he declared that "we have stopped Gadhafi's deadly advance." This morning, however, we see that Qadaffy's forces have regained the initiative. No one has a credible prediction for how long this see-saw keeps tottering. We seem to be headed for a protracted conflict we can ill afford. But you don't have to stipulate to any moral ambiguity on either side to worry that mission creep and the law of unintended conseuences could drag this out indefinitely.

I'd like to be wrong about this; I'm still in the "asking questions" phase – which may actually last for several years after this ends. So the next question is: where does this end?

No comments:

Post a Comment