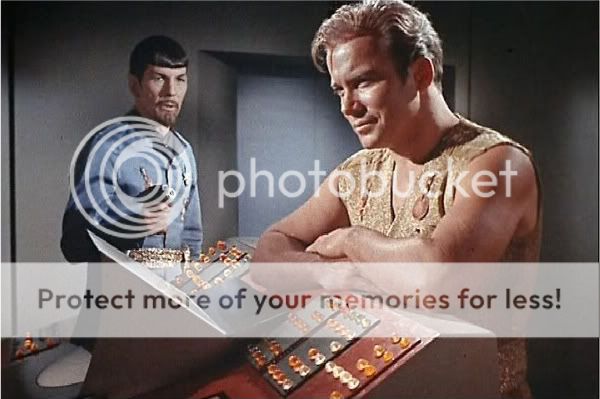

Moreover, of course, just having this over with is small comfort, since it's bound to be a bad deal – though the extent to which it's an evil-Spock/anti-Keynes deal remains to be seen. Whippersnapper Matt Yglesias suggests a bad deal was inevitable:

The rumored deals flying around Washington today all sound pretty bad. And how could they not be? The White House started with a position that:

1. Failure to raise the debt ceiling is unacceptable.

2. The country should enact substantial deficit reduction in 2011.

3. Any deficit reduction package must include revenue increases.

But (1) and (3) were in significant tension. The White House strategy for getting (3) was to persuade the public that (3) was the correct position. They did that, and all polls showed that public opinion was on their side. But then an underpants gnome problem arose. They didn’t dissolve parliament and call for a snap election. Eric Cantor said “no” and once he said “no,” (1) collided with (3) and the White House dropped (3). Once you’re there, how is the deal not going to be bad?Meanwhile whippersnapper Ezra Klein likewise opines that failure was always an option:

It’s difficult to see how it could have ended otherwise. Virtually no Democrats are willing to go past Aug. 2 without raising the debt ceiling. Plenty of Republicans are prepared to blow through the deadline. That’s not a dynamic that lends itself to a deal. That’s a dynamic that lends itself to a ransom.On the other hand, greybeard BooMan argues that Obama played his cards about as well as could be expected:

Let's look at where we stand this weekend. As soon as the ink was dry from the 2010 midterm elections it was clear that we would be seeing something never seen before. We would be seeing a link between raising the debt ceiling and cutting the deficit dramatically. I believe MSNBC host Lawrence O'Donnell discussed this on the air on election night, or within days of it anyway. So many new members had pledged to make this link that it was inevitable that the link would be made.

How did the president respond? At first he made the obvious argument that such a linkage had never been made before and should not be made now. But it wasn't something the Republicans could be deterred from doing by mere rhetoric. In fact, raising the debt ceiling polls very poorly and educating the public about it would entail a months-long effort to justify the government's inability to live within its means. The president's mission wouldn't be merely to improve those poll numbers to parity, but to convince an overwhelming number of people so that immense pressure would be placed on Republicans serving in conservative districts to abandon their linkage. This would have been an impossible task, even if his own party remained united behind him. But they wouldn't have remained united; increasingly they would have become divided.

As should be obvious by now, the new Speaker of the House never had the votes to pass a clean hike in the debt ceiling. He never had the votes to pass any reasonable or acceptable or even sane hike in the debt ceiling. And this wasn't any great secret. By no later than early spring it was clear that decoupling was impossible and that some deal must be struck. It was also clear before long that the Speaker couldn't deliver any fair or reasonable deal. What I'm saying here is that our present situation was not avoidable. We should not be debating why we're debating the debt ceiling. We're debating it because we lost the 2010 midterms, badly, to a bunch of fire-breathing debt-crusaders. It's fair to place some blame on the president for those midterm losses, but we have to keep things in context.

There's much to agree with in BooMan's defense of BHO-Man. The problem for me is the line I bolded at the end of that last paragraph. IIRC. the president was using anti-Keynesian rhetoric long before the midterm elections, and gave up on Keynesian economics well before the GOP forced his hand. Some of that was baked into the peculiar results of the '08 legislative races, with the bad luck of Al Franken's contested race and Ted Kennedy's brain cancer.

But if we're talking about how well BHO has played the cards he's been dealt, we also have to talk about how effectively he played cards available to him to influence the outcome of of the '08 and '10 legislative races. He had a tremendous war chest in '08 and a floundering opponent. There were grumblings at the time that a few cash infusions could have swung a Senate seat or two the other way (the GOP wins in Kentucky and Georgia were surprisingly close). There were grumblings as well that placing Napolitano, Sibelius, Salazar and Vilsack in the cabinet removed some formidable '10 Senate contenders from contention, as well as any incentives for John McCain or Chuck Grassley to behave themselves. (Never mind the decision by BHO and party leadership to support the Connecticut for Lieberman Party nominee in '06 instead of the Democrat.)

But the place where the grumblings were loudest, both inside and outside the White House, was the debate over the size of the stimulus. Hindsight is 20/20, but plenty of people at the time (no link required) could see both that the stimulus was too small to fully jumpstart the economy, and that consequently it was likely to affect the results of the '10 midterm elections. The way that hand was played means that the player has fewer chips to bargain with today.

No comments:

Post a Comment